Halfway across the Atlantic Ocean, the plane carrying Tani Sanchez and her daughter Tani Sylvester on a heritage tour to Ghana crossed paths with a powerful storm.

A sharp drop in elevation hurled flight attendants to the floor. Passengers started screaming and crying.

“‘Oh my God, I brought my mom! What did I do?’” Sylvester, 40, recalled thinking as the plane shook. “It was the scariest thing that has ever happened in my life.”

After a few minutes, the pilot pulled the aircraft to safety above the dark clouds.

Looking back, Sylvester sees the moment of terror as a nudge from the past, an invocation of the suffering of millions of Africans who were crammed into the lightless hulls of ships and sent in the opposite direction during the centuries-long transatlantic slave trade.

“I think my ancestors were telling me, this wasn’t an easy trip for us,” she said.

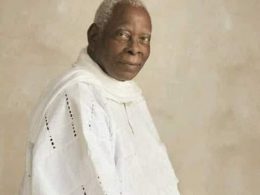

Tani Sanchez and her daughte Tani Sylvester in Ghana. Reuters Photo

“They sailed over that same Atlantic Ocean. It was traumatising and scary for months, and I experienced five minutes of trauma and I was freaking out.”

The two Tanis are among a growing number of African Americans exploring their ancestral roots in Ghana, which has encouraged people with Ghanaian heritage to return in honour of the 400th anniversary of the first recorded arrival of African slaves to English settlements in what would one day become America.

They had set off the previous day from Los Angeles, where Sylvester works for a digital-streaming service. But their family’s journey began nearly two centuries before on a sugarcane plantation in Louisiana – and, before that, the homeland to which they were bound.

THE ‘LITTLE BITTY’ SLAVE

Sanchez’s great-great-grandmother Mary Ann Moss was born into slavery around 1838. Moss was a “little bitty lady” with long hair pulled back in a bun who was tough from growing up as a house slave on a Louisiana sugarcane plantation set on an isolated bluff. After obtaining permission from her master, she married her first husband according to slave custom by jumping across a broom together. He died at his plantation; no one knows how.

After the Civil War, she married a black former Union soldier from the North named Charles Wright who had moved to Louisiana to seek his fortune. Wright so cherished his memories of serving in a Union regiment that he kept his uniform carefully preserved in his home and was often called “Soldier” by family and friends.

The couple prospered after Wright bought his first piece of land, where he established orange groves and grew apricots, pears and pecans. They had six children, but only three survived childhood.

They lived in a well-appointed home filled with old-fashioned furniture and canopy beds and would go to church every Sunday in a stylish buggy pulled by “fine big old red horses.”

TRACING A FAMILY’S HISTORY

These stories from a beloved grandmother about the family’s experiences through slavery, the Civil War and early 20th century America sparked Sanchez’s lifelong quest to discover her ancestry.

Using oral histories, court transcripts, land deeds and census documents, Sanchez, who is an associate professor of Africana Studies at the University of Arizona, gathered enough information to form a clear picture of the past few generations on her mother’s side.